|

|

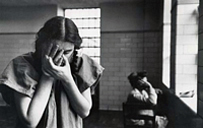

A protégée of Roy Stryker at the U.S. Office of War Information and subsequently at Standard Oil Company (New Jersey), Esther Bubley (1921-1998) was a preeminent freelance photographer during the "golden age" of American photojournalism, from 1945 to 1965. At a time when most post-war American women were anchored by home and family, Bubley was a thriving professional, traveling throughout the world, photographing stories for magazines such as LIFE and the Ladies' Home Journal and for prestigious corporate clients that included Pepsi-Cola and Pan American World Airways. "Put me down with people, and it's just overwhelming," Bubley exclaimed in an interview. Like most great photojournalists, she found her art in everyday life, and she successfully balanced her artistic ambitions with the demands of commercial publishing. Edward Steichen, curator of photographs at the Museum of Modern Art and the era's arbiter of taste, was a great supporter of Bubley, whose work embodied his aesthetic ideal that photography "explain man to man and each to himself." She was shown in several group shows at the Museum of Modern Art and was given a one-person show at the Limelight, Helen Gee's legendary coffee house and the only gallery specializing in photography in New York during the 1950s. Bubley worked primarily for the printed page, however, and like her colleagues, can be only partially understood in the context of today's gallery-oriented photography world, in which photographs are shown as isolated works of art. Bubley was a superb industrial photographer, capable of creating striking modernist patterns in black and white and color under technically challenging conditions. She was also a "people photographer" with an uncanny ability to achieve intimacy with her subjects and to construct subtle and complex narratives through sequences of photographs. Bubley's photographs are of cultural as well as artistic interest. Her photo-essays explore the era's American stereotypes—the troubled child, the high school drop-out, the harried housewife, the enterprising farm family—that were elaborated in the pages of the magazines for which she worked. Her corporate assignments document the introduction of American companies into traditional cultures abroad. Bubley developed a specialty in stories about health care and mental health, documenting the era's faith in new technologies and the growing prestige of psychology and psychiatry. She also covered her share of celebrities and popular culture topics, including children's television and beauty contests. A cross-section of Bubley's work provides a revealing glimpse into the post-war decades, seen not only through Bubley's lens but through the pages of the illustrated magazines that dominated the mass media of the time. Born in 1921, Esther Bubley was the fourth of five children of Louis and Ida Bubley, Russian Jewish immigrants who settled in northern Wisconsin. Although Louis later developed a successful auto parts business, the family struggled through the Depression with Ida helping to support the family by running a small-town general store. Esther's interest in photography, which began in high school, developed in college during her two years at Superior State Teachers College and a third at the Minneapolis College of Art. In 1941 at age twenty, she ventured to New York City to become a professional photographer. After a brief stint at Vogue, she moved to Washington, D.C., where war-time jobs for women were plentiful, to shoot microfilm for the National Archives. Bubley's career was launched in the fall of 1942, when Roy Stryker hired her as a darkroom assistant at the Office of War Information (OWI), successor of his nationally renowned Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographic unit. With Stryker's encouragement, she began photographing in Washington, and shortly thereafter, he sent her on assignment and contributed her photographs to the OWI files. In late 1943, when he left the government to set up a public relations project for Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) (SONJ), Stryker hired many OWI photographers, including Gordon Parks, John Vachon, and Bubley. At SONJ, Stryker continued the photographic documentation of American life that he had begun for the federal government. Interpreting his mission broadly, he dispatched his photographers all over the country to show that "there is a drop of oil in everything." Bubley is best known today for two early SONJ projects: a 1945 portrayal of the oil town of Tomball, Texas, and the 1947 "Bus Story," which spotlighted the role of long-distance bus travel in American life. She traveled far and wide -- from Minnesota iron mines to Massachusetts onion fields to North Carolina paper mills -- producing monumental depictions of industrial and agricultural labor. After Stryker departed Standard Oil in 1950, leaving 55,000 photographs in its archive, Bubley continued to work for the company. She traveled to Europe, Asia, Australia, and Central and South America, often combining SONJ work with assignments for other corporations. Her 1952 SONJ photo-essay on Matera, an Italian town transformed by the construction of a hydro-electric dam, and her 1954 photo-essay for UNICEF on treatment of the eye disease trachoma among the desert inhabitants of Morocco, are considered her crowning achievements outside the United States. Stryker moved from SONJ to Pittsburgh, where the city's university asked him to establish a photographic project. In 1951, he hired Bubley to document the Pittsburgh Children's Hospital. The following year, Steichen featured Bubley's Pittsburgh work in the prestigious "Diogenes With a Camera" series at the Museum of Modern Art. These photographs mark a shift in her style, from a carefully choreographed manner recalling Normal Rockwell's anecdotal Americana, or the heroic rhetoric of social realism, to a more spontaneous, intimate form of narrative. Although she had mastered artificial light and many camera formats, Bubley increasingly relied on the small, flexible 35mm camera and natural light. Photographs like those capturing an emergency tracheotomy in the hospital's hallway convinced her of what she could do without preparation. While working for Stryker and corporate clients, Bubley became a regular freelance photographer for numerous national magazines. She produced many photo-essays and several cover stories for LIFE, the nation's most prestigious magazine with a circulation of 24 million. Bubley's most ambitious magazine project, however, was "How America Lives" for Ladies' Home Journal, a celebrated series which ran intermittently between 1948 and 1960. Among the families interviewed and photographed were the Roods of Wahoo, Nebraska, who paid off a forty-year farm mortgage in six years; the Schmidts of Cincinnati, who despite incompatible Rh blood factors, produced four healthy children; the Simons of Los Angeles, who avoided divorce through psychotherapy; and the Colemans of Manhattan, who aspired to a house with a yard in the suburbs. Bubley also produced "How Young America Lives," about young families, and "Profile on Youth," about teenagers. These stories, rich in anecdote, reveal the preoccupations of American women of the 1950s. By the mid-1960s, television replaced magazines as the primary source of news and entertainment, undermining the demand for top photojournalists like Bubley. After twenty years of extraordinary productivity and exhausting travel, she accommodated herself to the change, reducing her workload and readjusting her ambitions. Briefly married in the late 1940s to Edwin Locke, a writer who also worked for Stryker at SONJ, she avoided domestic attachments and treasured her large midtown Manhattan apartment as a symbol of her personal accomplishments. A passionate gardener and pet owner, she published several books in the 1960s and 1970s about plants and animals. In the 1980s and 1990s, photography specialists, often investigating Stryker, rediscovered Bubley. Three books showcasing her photographs - images of children, New York sites funded by the Rockefeller family, and a Charlie Parker jam session - were published in this period. Her prints have been acquired by museums including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Library of Congress, the National Portrait Gallery, George Eastman House, and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. In 1990, the art department of the State University of Buffalo organized a small Bubley retrospective, and in 2001 the UBS/PaineWebber Art Gallery showed a comprehensive retrospective, which continues to travel.

|